Cheek epithelial cells

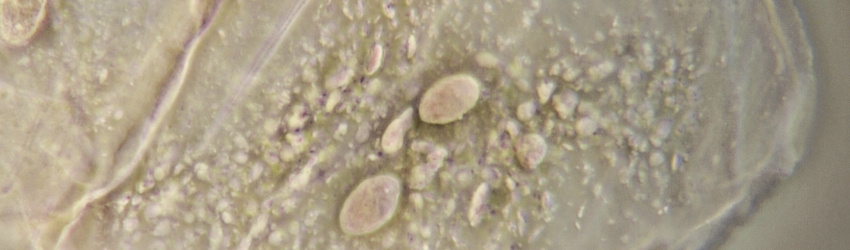

The inside of the oral cavity is covered with a layer of squamous epithelial cells. These are relatively large, flat cells that are constantly being produced and rejected by the oral mucosa. It is quite easy to examine these cells microscopically. To obtain some material, a toothpick is scraped along the inside of the cheek. The material is then suspended in a small drop of water on a microscope slide and covered with a coverslip. Someone with a less trained eye may have some difficulty seeing the epithelial cells; they are completely colorless and transparent. Reducing the opening of the aperture diaphragm will help in the observation as it increases the contrast but care must be taken not to lose too much resolving power. With a 10x objective, the cells are already reasonably visible, but to see more details we need a 20x or 40x objective. In normal brightfield illumination we see large cells with a clearly visible nucleus in the center of the cell and regularly some smaller so-called micronuclei can be seen. Micronuclei contain separate chromosomes or chromosomal fragments and are an indication of damage. The cells furtermore contain a lot granular material consisting of keratohyalin.

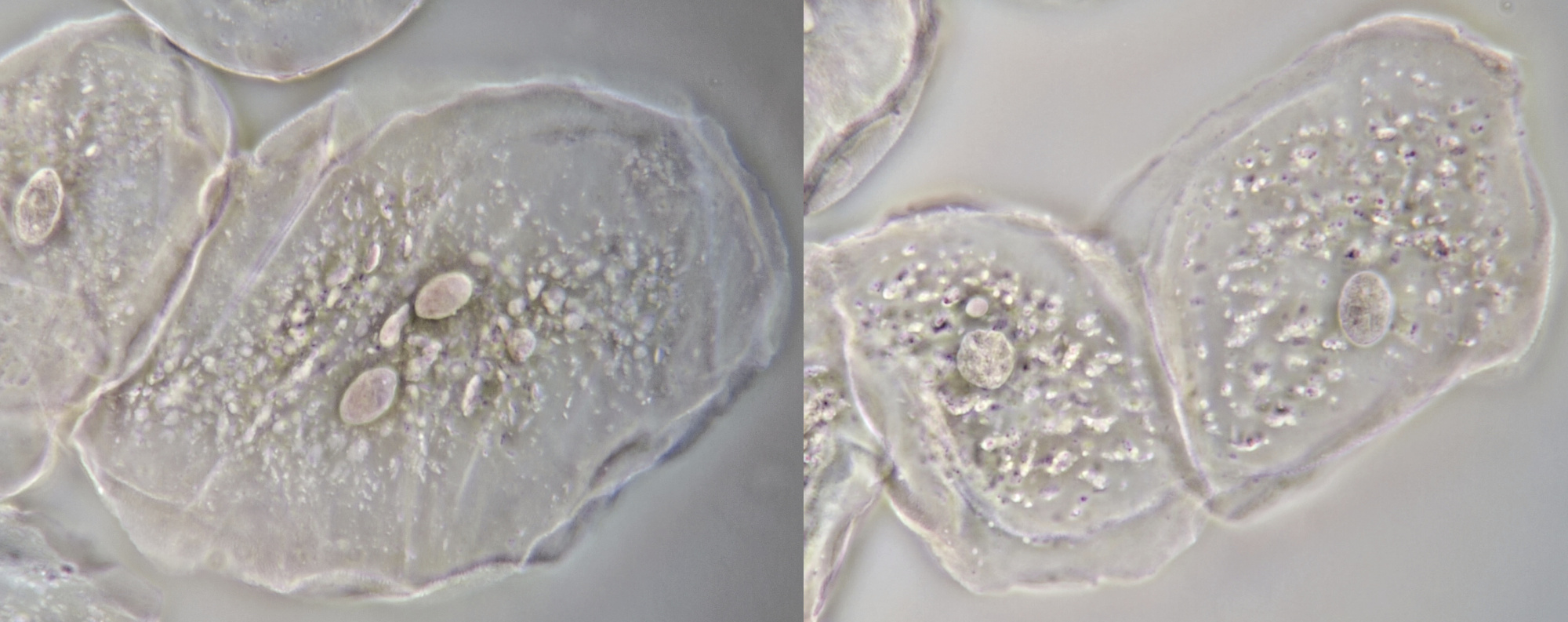

Cheek epithelial cells seen in normal brightfield illumination. Even without contrast enhancing methods, enough details can be seen including the nucleus in the center of the cell. Objective: Carl Zeiss Neofluar 63/1.25.

To make the details in cheek epithelial cells even more visible, special illumination techniques such as phase contrast, darkfield illumination and (circular) oblique lighting can be used. These techniques are also discussed in the technique section. Another way to enhance the visibility of transparent objects is by using a staining method. Cells can be stained stained with a dye like, for example, methylene blue. I once had methylene blue in the house, but it was not for long. If you accidentally spill something, you will have stains that are almost impossible to remove. In general, I have a strong preference for increasing the contrast with optical means.

Epithelial cells visualized with annular illumination. This technique increases contrast and gives a spatial impression of the object. Objective: Leitz Pl Apo 25/0.65.

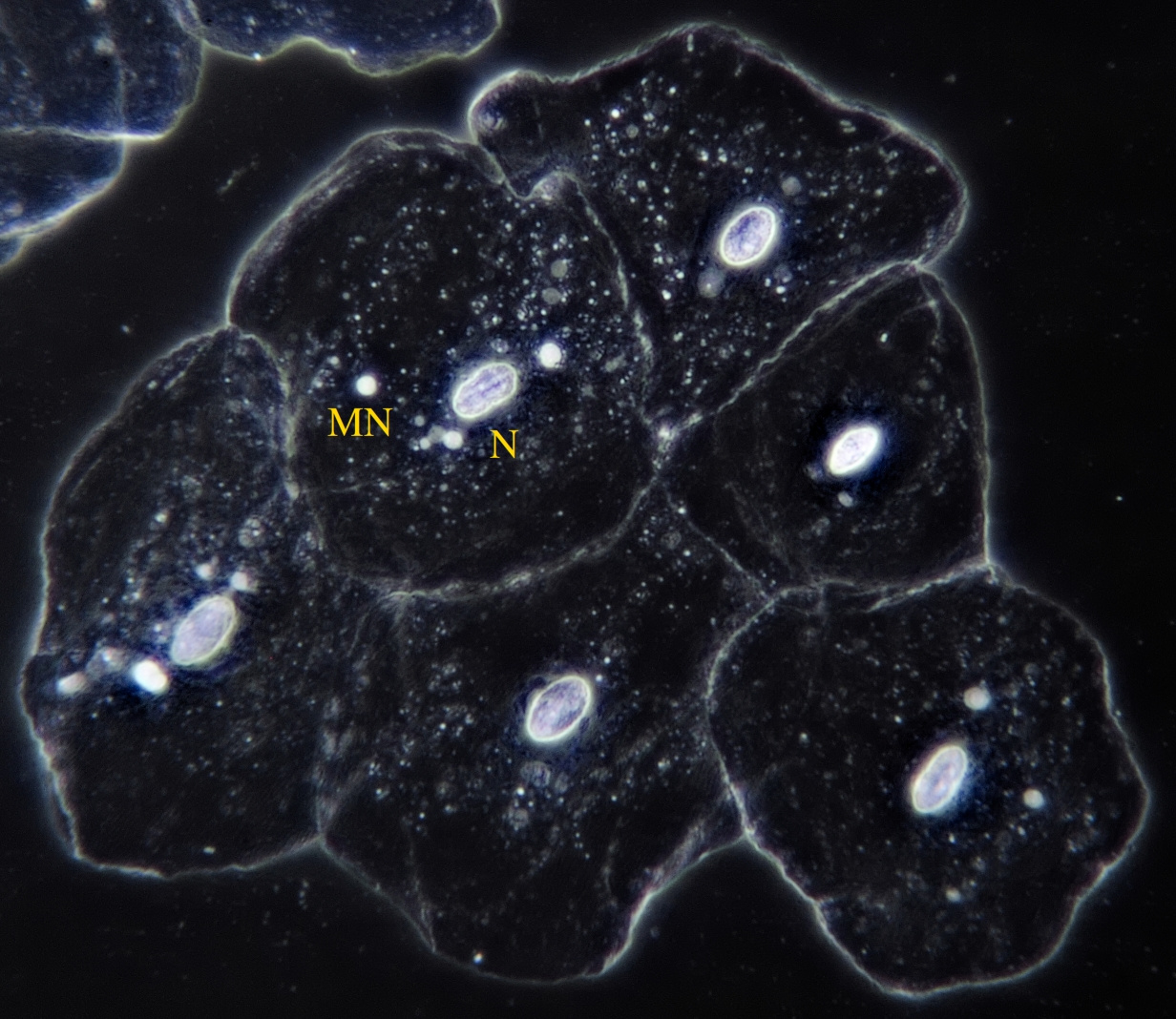

With almost any microscope it is possible to realize darkfield illumination and this technique is extremely suitable for making colorless transparent objects visible. With darkfield illumination, the cone-shaped illumination illuminates the object at an angle and the light is subsequently reflected by the object. The cells will light up against a dark background.

With darkfield illumination, nuclei (N) and the smaller micronuclei (MN) can clearly be seen. This image also shows how the cells are positioned in the original tissue. Objective: Leitz 25/0.50.

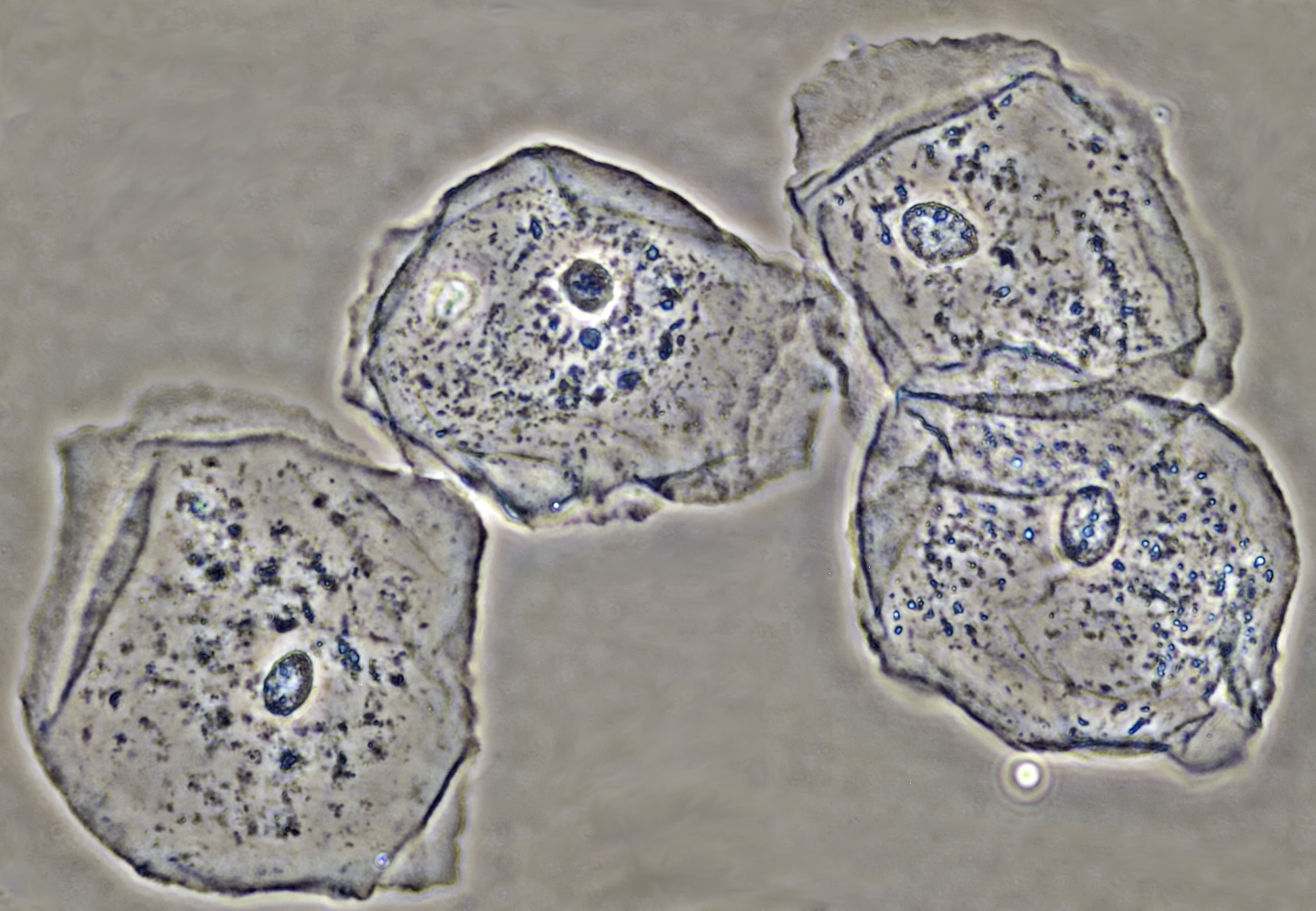

And then there is the phase contrast technique, a technique that is actually best suited for these types of cells. Details that were previously very difficult to see will become visible due to phase differences.

Epithelial cells seen in phase contrast. Objective: Leitz EF 40/0.65 PHACO 2.

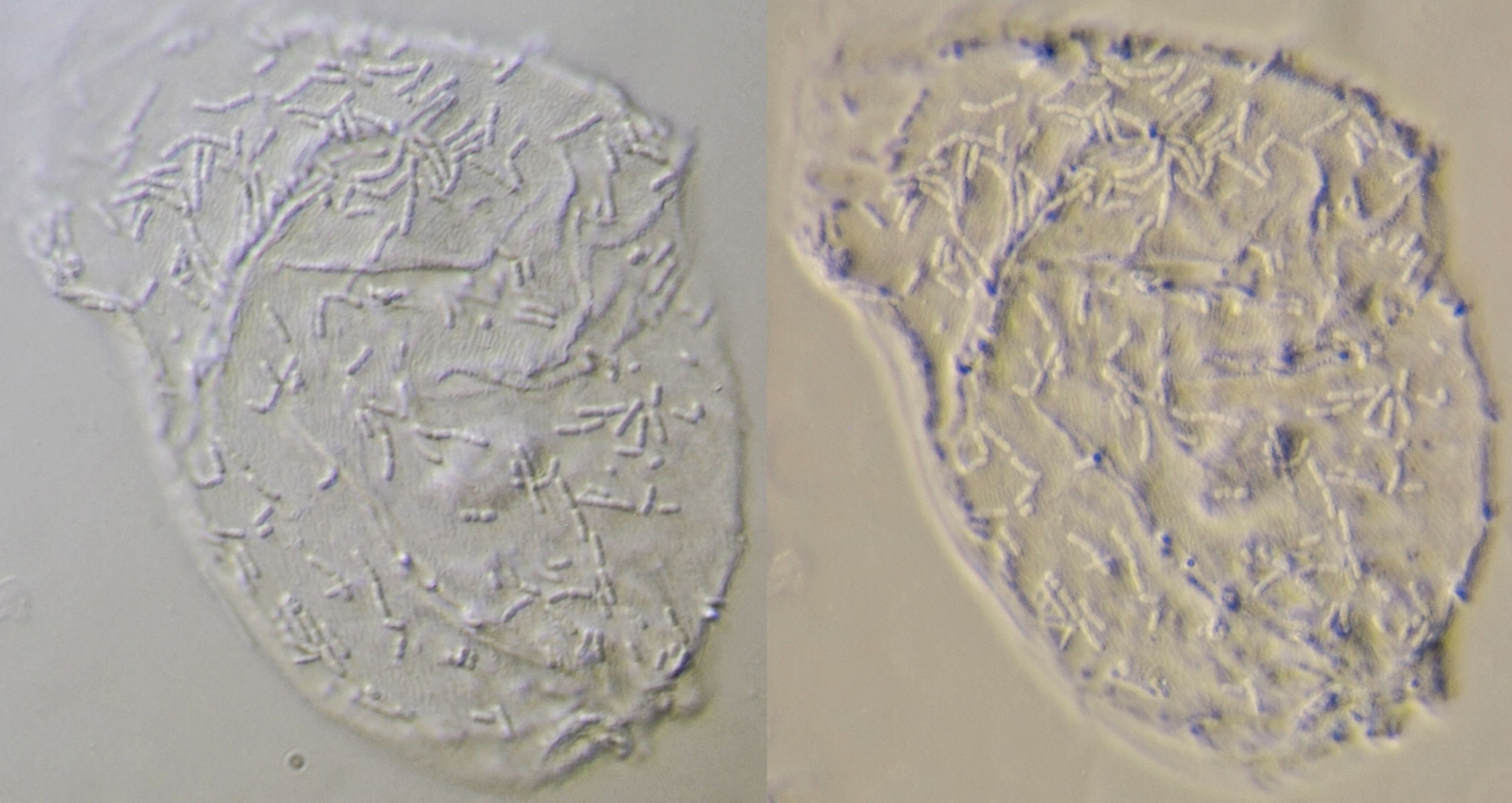

Sometimes you will see a lot of bacteria on a cheek epithelial cell. The image below gives a good impression of the size relationships between epithelial cells and bacteria.

Bacteria on a cheek epithelial cell visualised with oblique illumination (left) and annular illumination (right). Objective: Leitz NPL Fluotar 40/0.70.

Saliva

If you look at saliva through a microscope, you will discover that quite some bacteria live in there. They were already observed in the 17th century by Antoni van Leeuwenhoek who used a very simple microscope that contained only a single lens and with which a magnification of 250x could be achieved. The oral flora consists largely of streptococci, small spherical bacteria that are mostly arranged in chains. When not arranged in a chain, these are quite difficult to see with a microscope because they are very small and hard to distinguish from all kinds of debris that might be present in the saliva. The larger rod-shaped bacilli and motile bacteria, including some spiral-shaped spirils, are easy to spot.

To detect bacteria in saliva, you need a reasonably trained eye and you need to know what to look for. A technique such as darkfield illumination or phase contrast can help to increase the visibility of bacteria. With phase contrast, bacteria are visible as black shapes as shown in the following video.

Video of bacteria in saliva seen in a time-lapse phase contrast recording. A large filamentous bacteria can be seen in the foreground on the left. A twisting spiril is visible on the right. In the background, many small mobile bacteria are present. Objective: Leitz Phaco 40/0.65.

In addition to bacteria and epithelial cells, there may also be leucocytes present in saliva. During inflammatory processes in the oral cavity, the number of leucocytes in saliva is likely to increase. You can sometimes see dead leucocytes in which small particles are moving due to the Brownian motion.

A white blood cell showing Brownian movement of intra-cellular particles. Time-lapse phase contrast recording. Objective: Carl Zeiss Neofluar 40/0.75 Ph 2.

Literature

Jyoti S, Khan S, Afzal M, Siddique YH. Micronucleus investigation in human buccal epithelial cells of gutkha users. Adv Biomed Res 2012;1:35.

Susmita Dutta & Min Bahadur (2016) Cytogenetic analysis of micronuclei and cell death parameters in epithelial cells of pesticide exposed tea garden workers, Toxicology Mechanisms and Methods, 26:8, 627-634, DOI: 10.1080/15376516.2016.1230917

Nefić, Hilada & Mušanović, Jasmin & Kurteshi, Kemajl & Prutina, Enida & Turcalo, Elvira. (2013). The effects of sex, age and cigarette smoking on micronucleus and degenerative nuclear alteration frequencies in human buccal cells of healthy Bosnian subjects. Journal of Health Sciences. 3. 196. 10.17532/jhsci.2013.107.